Equities In Dallas

“Risk comes from not knowing what you are doing” – Warren Buffett

Most people end up on Wall Street for one of two reasons: 1) a genuine curiosity and interest in the financial markets which they would seek out whether they got paid for it or not or 2) a genuine desire to make as much money in as little time as possible.

For the most part this is a sliding scale with the bulk of people skewed towards the making money side who have no business being in the industry other than to make a quick buck so they can “get out to pursue their real passion.” Sadly, the group of people skewed on this side unfortunately often times end up being “lifers” in a job that they don’t necessarily love due to the proverbial golden handcuffs which get harder and harder to escape from when they start adding a family, children, second mortgage, ex-wife, etc etc…

For the rest of us somewhere in the middle of that scale, the decision to pursue a career in finance usually comes from a series of experiences in our childhood that guide us down this path of capitalism. It might be the rush that you felt after making your first 20 dollars selling lemonade, or maybe it was your first experience hearing the shouting on a trading flow when your dad brought you into work on “Family Day”.

For me personally, there were a number of experiences which piqued my interest in finance but one of the most significant ones was the first time I ever read Liar’s Poker in college. Liar’s Poker was written by best-selling author Michael Lewis and it describes his experience as a bond salesman in the late 1980’s during the height of the mortgage bond market bull market. His honest storytelling of the glamour (and crudeness) of Wall Street during that era, and more importantly the exorbitant amount they were paid for not really doing anything at all, was enough to cement my future in the world of high finance.

One of my favorite parts of the book was when Lewis describes the Salomon Brothers’ training program for new hires. After the end of the program, the new analysts are “placed” into various divisions of the firm with the most coveted desk being the mortgage bond desk and the least desirable one being equities. But not just equities anywhere mind you, equities in Dallas, one of the smallest satellite offices of the firm.

The nightmare of ending up in Dallas got so bad that when a trainee would answer a question incorrectly in class the back row would sneer “Equities in Dallas!” and heckle the poor soul. Talk about locker room antics!

The thing is, in truth, bond traders are generally smarter than equity traders and credit analysts are generally smarter than equity analysts. (Sorry equity folks!). I’ve been an equity guy my entire career, but there’s a reason for this and I believe it has to do with the way that each side analyses risk.

A few weeks ago I wrote about the conventional process that most investors take which begins with establishing an investment objective with a specific return profile in mind.

With this goal-oriented mentality, a very simple way of looking at risk is what is the probability that you cannot achieve this goal. For example, let’s say you were training for a marathon. There is a school of thought in marathon training that says you should never run the full 26.2 miles during training but rather keep your longer training runs between 15-20 miles and rely on adrenaline on the big race day to get you to the finish line. In this case, the risk is that on training day, you don’t have enough fuel in the tank to complete the race.

The problem with assessing risk this way is that once again the focus is on the upside (completing the marathon) and the risk consideration only encompasses the failure to achieve the goal, but nothing beyond that. As bad as not completing a marathon would be, how much worse would it be if you injured yourself before the actual day of the marathon and couldn’t even compete?

When it comes to investing, rather than viewing risk as your inability to reach your investment goal, which is quantifiable, it is far better to assess how much one can lose (not being able to even compete in the marathon) and the probability of losing it.

After all, we all know that the amount of pain that comes from losing money far surpasses the pleasure that comes from making profits, and yet it is human nature to focus mostly on the upside without considering the downside.

This is where bond investors get it right

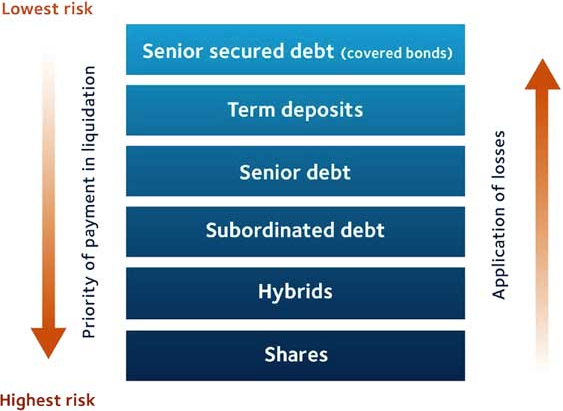

Equity investors often do not have a full understanding (nor do they care, for that matter) of the capital structure of a given company. There is irony to this in that bondholders are senior to equity holders in the event of a company’s liquidation. Equity holders always get paid last (which really means zero) compared to bondholders and so as opposed to modeling out discounted cash flow and forward earnings, equity holders should really take a page from bondholders who usually only care about two things: 1) getting their principal back and 2) earning a little bit of interest (coupon payments) along the way. The ability of a company to pay its debt obligations comes down to positive free cash flow which is very important to consider when we consider the risk of investing into a company.

Source: Morningstar

Remember, risk should be considered from the bottom up and baked into your investment process by means of a margin of safety. So the next time you go out there looking for the latest and greatest hot stock to invest in which will surely go to the moon, throw on your bond investor hat for a moment and look at what could possibly go wrong. When investors form a consensus and herd into a trade that everyone is giddy on, more often times than not, they are usually wrong. Do yourself a favor and don’t end up in Dallas!